Jesus sucked our sins from the world like venom from a snakebite. He puckered up and prepared to love, ingesting our evil in the process. He carried it to the tomb and let it rupture his insides. David was trying to remember this. He stood behind the station turnstile, trying to scan his Oyster. He laid the card down, and the light stayed red. He tapped it again, and nothing changed. He set all his weight against the turnstile’s walls and struggled to stay calm—thinking about the Lord; thinking about his word, about James and John and all of Jesus’s men who wrote the story of his life before he was around to read it.

The light went green. David fell through. Standing up, he straightened his tie and repositioned his bag. He was surrounded by people leaving for the world. They sped past him to catch their trains. Some went left, others went right, the brave brushed him aside, but David felt that all were watching, and he hated the weight of a gaze. He hated their eyes rummaging through his soul, looking for something to snatch at. If it was up to David, he’d relinquish his body, his skin, his fat, the moments they held, and become a spirit that ran through London’s streets. He’d still knock on doors and speak of damnation, but he’d do it free of the flesh. He’d be living proof—he felt you could call that living—that the Lord existed beyond the bones. But this body was his. The stubby fingers that worked at his collar were his. The eyes that, looking up, met the face of his companion Terry belonged to him. And only him.

Terry was a beautiful boy—not your typical Mormon. He had ragged black hair and a perfectly straight spine, and when he smiled you felt the world was all joy. It had been a long time since David had seen that smile.

The two men went everywhere together; Christ demanded it. They ate together and toiled together, they prayed together and slept together. When Terry used the bathroom, David stood outside and told Terry about his day. When David used the bathroom, Terry wandered off, and the piss rang out in silence.

They had been paired at the end of their training, stitched together by the Lord. It had been three months of fliers in bags, thirteen weeks of the Word on their tongues, ninety-one days of dismissive waves from people who couldn’t stand the sight of salvation. David was sure Terry had sighed the whole time. He could hear it now, that eternal groan, rushing out of Terry’s mouth.

David: “We’re a declining society. Aren’t we, mate?”

Terry turned away from the question and moved towards the platform’s stairs.

“Even our barriers are stuck.”

It was the middle of summer. The heat swallowed David. Pools of sweat colored his shirt. His soot black pants stuck to his skin. He writhed, subtly, unsuccessfully, before going Terry’s way. Terry knew him. Terry knew that he had found religion the same way he found anything, by letting someone else’s idea become his. Terry knew that David was 40 but balding, lonely but looking, ready to join the church but afraid of starting behind—yet he refused to show David grace. Terry was 19, the appropriate age to begin the mission. He hadn’t signed up to play caretaker. David had missed the boat. One was raised in the house. One didn’t move in late. One knew the rules—they were all one had. Though Terry was stuck with David now, he’d be sure to avoid him in Paradise.

Standing atop the stairs, David looked out. Here was the middle class: clutching their briefcases, pushing their prams. Here was Barnet: a town of quiet streets and lowered gazes. The bus ran 24/7, but the conductor drove most of its route alone. Strangers and friends walked past you alike. This was not a place where you were meant to meet. This was the end of the Northern line, a place you left. Leaving, David felt sorry for those who stayed. He wanted to pull the fliers out of his bag and throw them into their faces. He wanted them to know about Armageddon and be ready for it, but he knew, he had been told, that the real battle was to be fought in the big city, in Central London and Leicester Square, under electronic billboards and neon lights, near Shakespeare busts and giant clocks, at 5:01 and 5:02, over piles of litter and sleeping drunks, around people, moving, watching, performing people with places to be and things to do, lives to live and lessons to learn, people who would stop if you could change things for them, people David felt he could save.

He kept his fliers in his bag, and turned his eyes to the tracks, and followed Terry down the stairs.

Stepping onto the platform, David watched a train depart. The next Embankment-bound trip wasn’t for another seven minutes. Terry scowled at him as if he’d wished for this. The platform’s occupancy grew and grew, and with this David shrank. Each time an elbow grazed his arm or a knee rubbed his leg, he receded further into himself. The platform was full of happy people, smiling people, people with families, and people on phones, people with purpose who were on their way to find it, people he could not touch. Always, he felt soiled, stained. He did not want that for them. Opening up his bag, he grabbed his thermos and rubbed it against his forehead. Forcing a laugh, he whispered, “The old Herbal tea.” He put heat on heat as he continued to sweat, and murmured as the shame dripped down.

When one really got down to it, the body was the body. It was not a vessel, not something to be tamed. It was a thinking, living, entirely independent thing. It wrapped itself around the mind and pulled at the strands. Freedom from the body was death. One could not escape: not on this earth, not on this platform. Try as David might. He rolled his thermos over his head to remind his body that there was warmth in the world. He drank hot tea to burn the terror out. But this domestication was temporary. The body will not be tricked.

David, ever forlorn, was a man who had watched his life go by. He spent thirty years dreaming of success and ten years acting on it. Allowing a preoccupation to become a profession, he took the herbal tea his mother raised him on and started selling it for profit. The health-crazed elite bought his boxes by the dozen. The Mormons bought them when they could. Herbal tea was the only warmth the Word approved of, so the Saved spent their winters between the aisles of David’s store. It was how he met Terry. It was how he found the Lord. It was why he turned towards the Light when his tea began to sour.

Still whining, still hazy, with the thermos against his neck, David stumbled through the crowd and found himself on the platform’s edge. It was time to come to. He spotted Terry, now wearing his namecard, watching from a few steps back. He followed suit. He dropped the thermos into his bag and pulled out his badge. Working the pin through his shirt, he sighed as he remembered:

Elder Hillburn.

The Church of

JESUS CHRIST

of Latter-Day Saints

Wearing the badge was like advertising his fraudulence. He’d joined their team of missionaries after the deadline, so his order was placed separately. The budget printer David commissioned was untrained in the art of font. When the badge arrived, it appeared that David’s title had become a superscript and that his name was Jesus Christ.

Terry’s name was Elder Derstill. Terry’s badge was fine. Terry prayed that David would fail. David longed to forget.

He grabbed a stale biscuit out of his bag and chewed the thoughts apart. The voice on the loudspeaker reminded the crowd to stand behind the yellow line. David complied. Something brushed against his side, and spinning around he watched a crook-backed woman with fraying grey hair move through the masses. She whispered and wailed as she walked, sending a shiver of unease down David’s spine. There was a tugging at his ankle, and, quickly looking down, he saw a child, wearing strap-on fairy wings, wrapped around his leg. He grinned, lopsidedly, awkwardly, and let out a chuckle. “Bicky!” the fairy-winged girl said. And just as David reached down to give her a piece, the girl’s mother pulled her away. It was the badge, he thought, standing back up, creeping towards the yellow line. They knew that wasn’t his name.

Their ride was two minutes away. David wiped the crumbs off his face. A few groups to his left, the girl made a whooshing sound as she ran in circles around her mother. Accustomed to this game, the mother whirled around too. She spun and spun and begged her child to stay near, stay safe, stay away from strange strangers and stranger ideas. David huffed like the oncoming train.

Totteridge & Whetstone. The cart was packed. David had managed to secure a seat. One stop later, Terry slid onto another, directly across from him. They rode in silence. The train screeched underneath. The sound shot straight through David’s skull, and into his brain, making it difficult to complete a thought. He stared at himself across the aisle, watching as the window’s curve reflected his body over the axis of his featureless face. He was an hourglass: a body above, a body below, and an empty head in the middle.

When the train came to a stop at Woodside Park, the man to David’s left spilled coffee on his pants. He frowned, and David mirrored him.

“Got a tissue, mate?”

“I know the feeling.”

“But have you got a tissue?”

West Finchley. Terry’s eyes were on him. Finchley Central. The gaze would not budge. If it were possible, David would want to know exactly what others thought of him. Life would be easier if a bell went off each time his name crossed someone’s mind. Given the chance, he’d pull on his rubber gloves on and catalog the brains of those closest to him. He’d parse through the muck and pull out the cabinets until he came to the file that held his name. DAVID.

DAVID → DAVID_Impression → DAVID_Impression_Poor.

DAVID → DAVID_Youth → DAVID_Youth_Rough.

DAVID → DAVID_Interests → DAVID_Interests_Blank.

Well, no, perhaps that was unfair. He had interests, he felt he did, only people might not see them that way. He was interested in what interested others about him. He quite liked tea. And more recently he’d found himself passionate about the Word.

Take Jonah, for example.They’d read his book last week: A man so afraid of his life’s purpose that he threw himself into the ocean to avoid it. How fascinating. David loved the heroics of it all. No matter how loudly the thunder clapped and the waves came crashing down, God’s children would be saved, because the Bible was the book of redemption. Jonah was swallowed by a whale, a real-life whale, and still he survived and prayed and gave thanks to the Lord. He dragged the Word out of the beast and threw it into the world. This interested David—more than he could believe.

Arriving at East Finchley, the fairied girl began to laugh. The train had come up from underground and it would be nothing but light for the next few stops. She lunged over her mother’s shoulder and pressed her hands against the glass. Off, off, off the train went, and the girl flapped her wings along with it.

Terry pulled at his smile. He turned away from the girl and looked to David. David’s eyes met Terry’s and then quickly found the girl.

He felt far from her. Years away. He had nothing to laugh about. Nowhere to fly to. Only: envy. How was it, he wondered, that, even with her hands pressed against the world, she could stay clean. He’d rolled out of the womb all sticky, and it took him thirty-nine years to realize he’d been catching dust.

They had to know, all of them. David felt that they had to know. He had ticked his life away, and the regret was all over him. They knew his story. They were reading it now. “Lost,” on his arms. “Waste,” on his neck. “Hopeless,” across his forehead. He was thrown into life without a sense of direction. He had spent his early years inflating the world, and it was only a matter of time before it popped. Earth was hollow. It was empty. It had been made far too large to appreciate alone. He couldn’t say it in so many words–and who would listen if he could–but he’d felt he needed Terry, even in silence, to prove that the world was still there.

The whispering woman made her way down the cart. She was quiet now and pulling at her hair. Seeing her face-on, David thought she looked a little like his mother. She had the same wide green eyes, which tried to hold you, which tried to hold everything at once. They bounced around the train, and David tried to follow them. They bounced from window to window: David’s eyes bounced too. They bounced from advert to advert: David’s eyes continued. They landed on David, and, trying to meet his own gaze, he shut his eyes and suddenly saw his mother. She stood in the darkness of his mind, looking far younger than he’d ever remembered her. Only recognizable because even in her youth she had those same green eyes. She smiled. Her eyes called for him. He wanted to run into her arms, but he had no way to place himself inside of his mind, so he kept his eyes closed and watched. Realizing that he would not come, her smile broke. Her eyes moved this way then the next, but all darkness was the same. Her eyes shut, then shrank, then disappeared, and she began to age. She aged thirty years in thirty seconds, and died just as she did the first time. An old woman, collapsing in the dark, in front of a son who could not save her.

Highgate. David opened his eyes.

Carrying a clipboard, a single commuter entered the cart. She wore a Nirvana shirt and a fully-studded face. She stood in the middle of the carriage and looked around: at the elderly woman tugging at her locs and Terry losing to sleep and David looking at her looking at him looking at her: they held this for a moment, the train departed, and the Cobain fan began:

“Right! There’s a national crisis, and national means that you’re all affected. Even you, dude,” she said to Terry, whose eyes were now completely shut, “Sunak! Your Prime Minister doesn’t give a hoot about you. He doesn’t care if you’re on this train or under it. He spends his mornings doing photo-ops with firemen, nurses, schoolchildren, people he calls heroes, and his afternoons killing them. Rolling back climate agreements, signing shady deals. Fossil Fuels has a hand up his ass and they’re fiddling around in there like he’s a fucking puppet.” Archway. “Sign a petition. The future is now. Remove the man. Remove the man. Take our future out the can!”

At Tufnell Park David waved away her clipboard.

At Kentish Town she climbed off the train.

Now was here, it was there, it was gone, it was fleeting, running, slipping through his hands, it was crushing, a weight on a weight on a weight on a weight, all of which looked like air. It had David, it held David, it was all David had, so it was never, it could never, it would never be the moment when he let the Devil in.

Prime ministers. Petitions. It was all the same thing. It all wanted to turn his bodily years into something to be controlled. David knew that England had gone to the dogs, but his signature wouldn’t change that. If anything, he felt it was best to get life out of the way. To resign themselves to the world they created, and wait for it to devour itself.

Camden Town: again, darkness.

David lifted his head and began to scour the train’s ads: a weight loss pill called Fat(e), a new Starbucks size called Grandést. His eyes landed on an image of a woman and her children at the beach, captioned “Travelong: You can have it all.” She wore a seashell necklace that was more string than shell, and was staring, almost gloomily, at something out of the frame. David squinted. There was something she was trying to tell him. He pictured the inside of his brain and scratched through it for answers. It was easier this way, the whole thinking thing. He remembered that his early life had been characterized by feeling bad amongst the good. His mother’s love turned all things gold, but nothing felt like enough. The world was beautiful—palm trees and coconuts and their metaphorical equivalents—but the conditions of his life were barren, and there weren’t enough budget getaways in the world to change that. Now, saved, he was the good stuck in the bad. The world was ending, and all he could do was smile and try to pull people out of it. He gave his eyes a break, and the woman’s sadness reappeared. He couldn’t say which of them had it worse.

Somewhere between Mornington Crescent and Euston Terry had woken up. Rested now, on the way to city life, he was itching to get things started. He shuffled through his fliers like a pack of cards and greeted the train with a smile. David, for reasons he couldn’t scratch, felt less prepared to go. Looking at Terry, he itched inside: here was everything he could have been. Charismatic. Christened. Comfortable in the world. At 19, David’s only God was Success. He’d chased a dream, labored through life, clutched the spirit of the age. But when he opened his hands to survey the spoils, it appeared he’d held nothing but ash.

He sat and studied his trembling fingers. They were wrinkling. Old age would soon be here. He felt it, working its way into his joints. He saw it, right in front of him. He remembered his mother’s final days. How small she’d been. How often she’d ask for moments of his time, and how few he had to give. She’d say, “That’s my tea. That’s my tea. At least sit and drink it with me.” But he hadn’t a second to spend on a woman who was barely there.

David grabbed the thermos—cooler now—and pressed it to his face.

Jonah had to leave.

Warren Street.

The woman tugging her hair grew more and more violent. She opened her eyes and propelled them at David. They struck a nerve, and he was jolted back. Mutters began to spew from her mouth, whispers of Leicester Square and a past returned. David felt that she was cursing him. He felt that had to stop:

“A penny for your thoughts?”

“I’ve not got any change.”

“Have you lost your marbles?”

“They’re on thin ice.”

Staring at David, with her marbles long gone, the old woman tried to smile. She wore a butterfly brooch on her coat and the story of her woes in her eyes. She was mixing her metaphors, and mixing them well. She was going to Leicester Square so it would come back to her. She was marching to the sound of her own splitting hairs. The cats and dogs would be on her soon. She had no money; she held no change. She was a dime a dozen. She hit the nail on the head. She was bent out of shape. She felt under David, under the weather, under the weight of His words. She must be going now: control was heaven in a wrapper.

At Goodge Street, she ran off, stumbling into the wrong station.

The train moved on.

There was something about the way Terry smiled that made David hot in the head. It was an act. He moved like a celebrity: shaking hands and holding gazes. As though he was the one who wrote the Word. David had done all he could to impress the boy who radiated salvation. But seeing Terry now—bright white teeth framed between quivering lips—he was sure that the Light was the Lord’s.

The little girl with the little wings stood in the middle of the aisle swinging around a grab pole. Across the cart, she watched as David worked at his thermos and poured himself a cup. She flew towards him to ask for a sip but was intercepted by her mother’s aggravated hand. This time it heralded another: a palm right across the girl’s face. The woman pulled her daughter onto her lap and unleashed her words on her.

David wanted to give the woman a piece of his mind, to let her take it, keep it, be forced to live with it. He’d stuff it in her bag, and wait for her to find it. She’d be looking for a number or searching for a pen; she’d empty her bag onto the counter; she’d find him there, jiggling away, cold, pink, wet. Her husband would come home and, loosening his tie, declare that “there was a brain in the kitchen.” “That’s David,” she’d say. “Ah,” he’d reply, “and what exactly is David doing on our counter?” She’d explain that they met on the train; that he’d followed her home; that he’d come to point out her cruelty; that it was his mission to enlighten the world but some days it felt hard and most days he felt tired. He wanted her to know what he thought, and he didn’t want her to escape it. She’d have to deal with the mess.

But the world would stay clean, and David would stay still, and the woman, pulling her daughter by the ear, would step off at Tottenham Court Road, taking any chance at change with her.

He lifted his thermos to his head and groaned like they would understand.

There would come a day when all this was gone. The mothers, the teas, the Terrys would all face the eyes of God. Fire would rain down from the sky, and only the devout would be saved. Until then, trains would crash and angels would suffer and evil would wash over the world. They were drowning, and no one seemed to care. They stripped him with their eyes and dissected his soul. But could they account for theirs? He was saving others when he could barely swim himself. He was nothing. Nothing to Sunak to England to the world—Jesus Christ—he was nothing to the world.

He pressed the thermos down harder and thought of salvation. He pressed down some more; perhaps this battle was not his. He rolled the metal down his arms, up his chest, against his neck, and began to wheeze. Closing his eyes, falling into himself, he shrank, and writhed, and prayed the world would disappear.

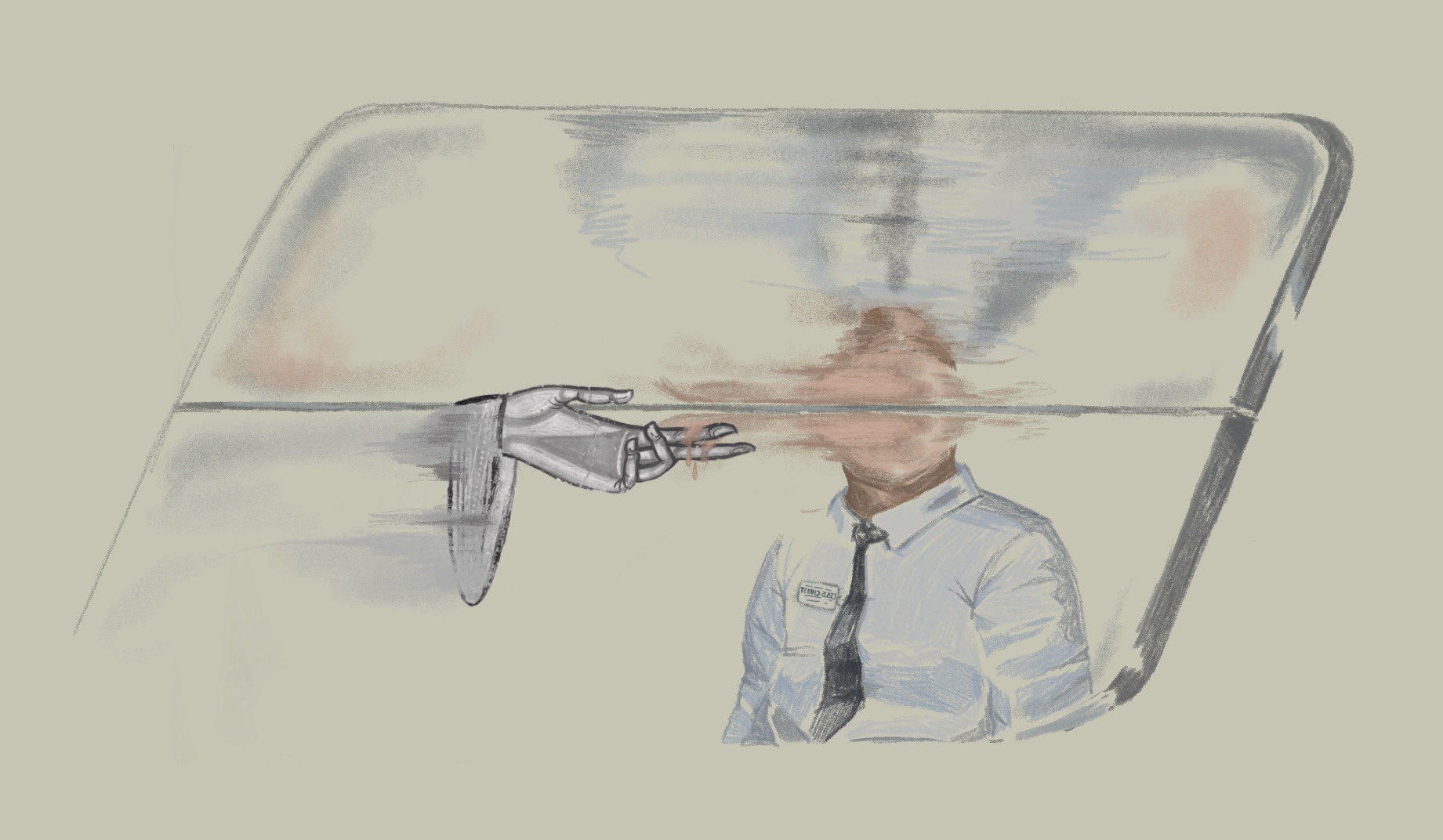

He had taken his life and wasted it, but he had walked in the Light at the end. At Armageddon, he would be spared. A beautiful bright hand would reach through the flames, and carry him into the house of the Lord. The choirs would sing, and the devout would applaud, and the hand’s fingers would wipe him clean. Gently. Caringly. They would hold his hands, and still them with love. He was the saved. Not the savior. Someone else could deliver the Word. Leicester Square.

When he returned to his body, the tea had spilled on his lap and Terry was outside of the train. He watched as his companion called his name to the closing doors.