Academic affairs: The love stories of Yale’s faculty

Married Yale professors shared their experiences living and working together at the University.

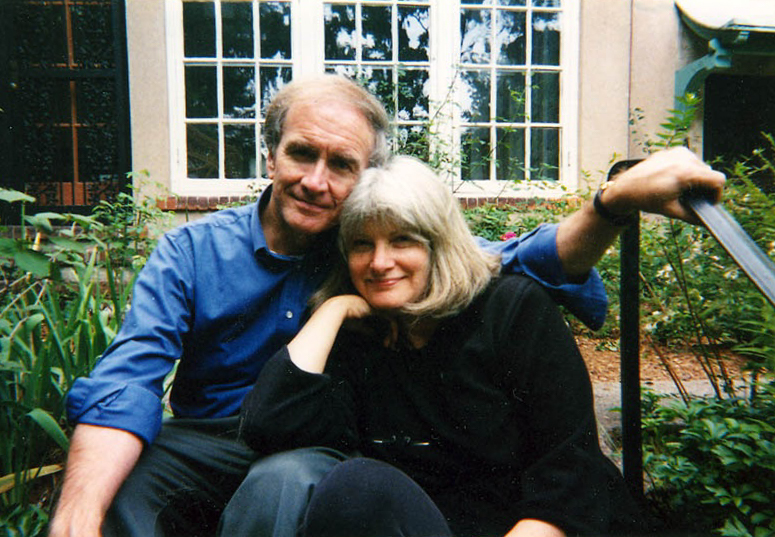

Courtesy of Toni Dorfman

Every year, Valentine’s Day proves that love is everywhere. Certainly, romance at Yale graces the lives of every community member, including the illustrious minds that comprise Yale’s faculty. Married life is always a lively adventure, and for professors who have found love within the University, Yale is inextricably bound to their love stories.

Dr. Karen Foster GRD ’74 ’76 and Dr. Benjamin Foster GRD ’74 ’75 met while attending the University as graduate students, and have been married for nearly 50 years. And until Karen Foster’s recent retirement, both taught together in the Near Eastern and Classical Languages Department.

“It’s astonishing to me to think that’s how long it has been that we have known each other,” said Karen Foster. “From the very beginning, we had a little two room apartment off of Orange Street in New Haven, and we shared a study.”

For professor of history John Lewis Gaddis, a job offer from Yale prompted a proposal. He met his wife, theater studies professor Toni Dorfman, when they both worked at Ohio University in the ’90s. Their relationship had only recently blossomed when he determined he would soon be leaving Ohio for New Haven.

“On the fourth date, after two weeks, I proposed, and the proposal line was: having just got tenure at Ohio University, which she had done, would you consider giving it up to move to the east coast with a guy you don’t really know, into a house you haven’t seen and without any assurance of a job?” recalled Gaddis.

Dorfman said yes “on the spot,” proclaiming: “I didn’t want John to outdo me in audacity!”

The couple spent a year long-distance dating through the telephone before Dorfman was able to join Gaddis as a professor at Yale. Dorfman said that she had not initially applied for a job and was hoping to take some time to settle into her new home when David Krasner, the then-theater studies director of undergraduate studies asked her to teach a single acting class. Apparently, Provost Alison Richard had sent out Dorfman’s CV to various departments at Yale, determined to find Dorfman an outlet to continue teaching.

Dorfman remains grateful to this day and describes how she keeps a picture of Richard scotch-taped to her desktop computer. For her, teaching at Yale has been a tremendous gift.

“You students are so brilliant, brave, honest and endearing, I’m forever learning from you, and I wouldn’t stop teaching for the world,” she said.

Gaddis and Dorfman were not the only couple facilitated by Yale hiring. Professor Laurie Santos, who teaches the highly popular course “The Science of Wellbeing,” finally mustered the courage to speak to her husband, philosophy lecturer Mark Maxwell, having spent months referring to him as the handsome “1369 Coffee House Guy,” just after accepting a job at Yale.

For the first few years of Santos’ employment, Maxwell would travel to New Haven from Cambridge, Massachusetts, to spend weekends together, times the couple fondly remembers as spent purely enjoying each other’s company.

“It certainly had never occurred to me that we would work together academically,” said Maxwell.

Nevertheless, after the two were married, Maxwell “followed” Santos to New Haven and enrolled at Yale as a graduate and then doctoral student in philosophy. He describes how the philosophy department “graciously” offered him a lecturer position and invited him to teach a couple of undergraduate classes.

“It was a relatively painless process for us,” said Maxwell. “I know some people go through fire trying to figure out where to be together.”

This certainly was the case for the Fosters. Benjamin Foster began teaching the year after his graduation, filling an urgent vacancy in the NELC department. Despite having the same doctoral degree, Karen Foster claims her husband was told by his superiors: “Oh yes, we know that your wife is eminently qualified. We know that she’s done all of these things. We know this, blah, blah, blah. We don’t want to hear a word about an appointment for her.”

Karen Foster remembers how during her senior year as an undergraduate student, her advisors warned her that institutions would be hesitant to hire her if she chose to start a family. The Fosters described how for almost two decades Karen Foster taught anywhere she could within driving distance of New Haven, sometimes going as far as Rhode Island and Massachusetts.

Karen Foster was even a finalist for a permanent position until the university in question learned more about her family life.

“It was quite discouraging and disillusioning to be the final choice of the search committee and all of that, and then to have some Dean say, ‘Oh, well, if you’re married, you don’t take us seriously’ and just withdraw the offer,” said Benjamin Foster regarding his wife’s experience.

Once a friend of the couple became the chair of the NELC Department, Karen Foster was promptly brought on as a Yale professor. However, in her 25 years at Yale, Foster never received the tenure her husband has enjoyed.

“Do I ever wish that I had tenure? Yes, but do I ever wish that I had not had an incredibly rich and satisfying personal life? No, never. I wouldn’t trade that for anything,” said Foster.

According to Foster, only three women in the NELC department have ever received tenure and none of them have had children.

Benjamin Foster told the News that a commitment to the “life of the mind” often requires academics to follow opportunities to distant locations. Despite the “stressful” years before Karen Foster joined him at Yale, he appreciates how their employment at the University allowed them to “stay together as a family.”

Sterling Professor Howard Bloch and professor Ellen Handler Spitz, bound by both love and scholarship, also share their lives as devoted partners and colleagues. In an unpublished essay chronicling their highly intellectual romance, Spitz reveals how she was first introduced to Bloch through his writing. A mutual friend had provided her with a copy of Bloch’s work, “One Toss of the Dice.” She read the book on a plane to Paris, where she had plans to meet him in person.

“High over the clouds as my plane sped across the Atlantic, I fell hopelessly in love,” she writes.

Their connection flourished over discussions about the book, which Spitz offered to review as a writer for The New Republic. Bonding over their mutual fascination with each others’ ideas, Spitz described their relationship as “an ongoing conversation that has continued uninterrupted ever since.”

The two take full advantage of their mutual employment, co-teaching a seminar entitled “Love, Marriage, Family: A Psychological Study through the Arts.”

Additionally, Spitz and Bloch both teach in the Directed Studies literature track. Grace Malko ’28, who is currently a student in Bloch’s Directed Studies section, describes how Bloch and Spitz have occasionally combined their sections for special presentations.

“They taught their two seminar classes together last week, and their dynamic is very sweet. You can tell they really do love each other,” said Malko, who is a staff writer at the News.

As scholars in the same department, Karen and Benjamin Foster are constantly working together and supporting the other’s projects.

“She reads all of my books and manuscripts and all of my major articles, and I read all of hers,” said Benjamin Foster. “I recently published a 1,000 page book, for example, and she read every single word of it and edited it extremely well, much better than a professional editor. So yes, I depend on her in many ways.”

The Fosters professionally collaborated on their 2009 book titled “Civilizations of Ancient Iraq,” which they co-authored. The book was inspired by a series of teach-ins they held on the region’s history.

“We have quite different ways of looking at material evidence and material culture,” said Karen Foster. “We were able to combine these two different perspectives and sets of insights into a unified book.”

Gaddis and Dorfman are also frequent collaborators, deeply in awe of each other’s passion and expertise in their respective fields.

“Toni is a regular in coming into my seminars,” said Gaddis.

In fact, he recalls he first became enamoured with Dorfman when he invited her to give a lecture on the First Balkan War in his contemporary history course.

“I thought since I was teaching about it that it would be fun for her to visit my seminar and talk about dramatizing history. And so she came sweeping in dramatically, red scarf flowing behind her. The history students had seen nothing like this, and I hadn’t either. So I thought that was really something special.”

All too familiar with this story, Dorfman laughs and clarifies she never wore a red scarf. All the same, her bold, theatrical approach to historical content left a lasting impression on Gaddis. Their relationship has similarly changed the way Dorfman thinks about history.

“Historians are people who turn something that happened into a story with a beginning, a middle and an end. That’s exactly what we do in the theater,” Dorfman told the News. “We tell storieswith an arc like that, and both of them are supposed to help us understand ourselves and the world better.”

For Gaddis and Dorfman, their academic pursuits play a crucial role in their domestic life.

“We have a surprising number of common interests, I think, and we never get tired of talking about our students. We have enough difference in our topics and what we teach that we’re always learning something from each other,” said Gaddis. “Every night, when we have had a full day of teaching, come home and we either watch some television series or, more likely, just talk about our students — sometimes for an hour — talk about our students and the questions that arise in our seminars.”

Similarly, shared scholarly passions facilitated Santos and Maxwell’s initial romantic connection. Maxwell recalls how early in their relationship they traveled together to Puerto Rico, where Santos was conducting studies on monkeys and Maxwell served as her research assistant.

“This is a thing about being a nerdy academic, we like to share ideas, right?” said Santos. “When I was an undergrad, I was just like: that is what I would want someday in a partner. I want someone who will lie awake with me at night and wonder about the brain. And we always wonder about the brain. Mark has a habit of wondering about all kinds of weird things.”

Working together at Yale has yielded numerous benefits for Santos and Maxwell. They enjoy having the same vacation days and have conveniently found they can help each other figure out “who to email” when interacting with the administration. The two make the most of their life together in New Haven, and love to attend Yale colloquia and interesting speaker events. They even got married locally in Sleeping Giant State Park.

For Gaddis and Dorfman, working together at Yale has enabled them to find community. They love to host students for dinner in their New Haven home.

“We think it’s wonderful, because it is kind of like a family. We feel like we have hundreds of children for whom we have no financial responsibility!” said Gaddis.

There is perhaps no more romantic setting than New Haven, Connecticut, where love giddies the hearts of undergraduate freshmen and tenured professors alike.

For those of us who are lucky, perhaps this is what Yale University can be: a place for minds to fall irrevocably in love.

Carl Eifler ’70 and Deborah Johnson ’71 were the first Yale students to be married on Aug. 8, 1970.